Harvey Milk, California’s first openly gay politician, believed that the city’s LGBTIQA+ citizens deserved a symbol that celebrated their love and the power of the Gay Liberation Movement. At the suggestion of Milk and activist Cleve Jones, Baker designed the rainbow flag. The two flags produced for the 1978 Gay Freedom Day Parade were hand-dyed and stitched, and measured more than nine metres in length. The coloured stripes on the flags were each assigned an arbitrary meaning: hot pink for sex, red for life, orange for healing, yellow for sunlight, green for nature, turquoise for magic, blue for serenity, and violet for spirit.

The following year, Baker worked with the city’s Gay Freedom Day Committee and Paramount to create what he described as a ‘landscape of rainbow flags’ for the 1979 Gay Freedom Day Parade. Four hundred flags were produced and attached to lampposts along Market Street. To ensure no part of the flag was obscured by the post, Baker removed the turquoise stripe. The resulting six-striped version is now considered the standard design for the rainbow flag.

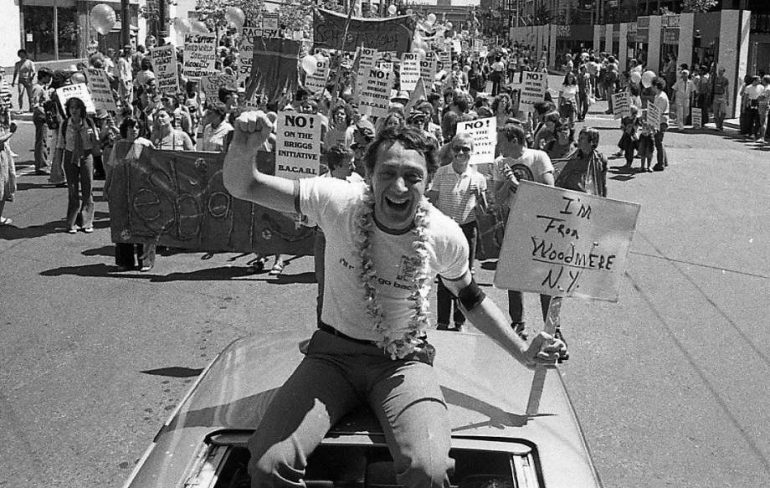

Use of the flag by the city’s LGBTIQA+ community increased in response to Harvey Milk’s assassination on 27 November 1978, after which San Francisco’s Pride Parade Committee officially endorsed the rainbow flag. A combination of increased demand following Milk’s death and a shortage of hot-pink fabric led to the flag’s only manufacturer, Paramount Flag Company, selling the flag without a pink stripe.

Hosting or participating in events and webinars can be a powerful way to engage your audience. These live interactions offer a direct and personal touchpoint with your brand. Plan regular events or webinars around topics of interest to your audience, and use design to create captivating visuals and promotions. The interaction and value you provide during these events can leave a lasting impression, strengthening your brand’s presence.

Baker was also motivated by the revolutionary function of the flag and their creation throughout history as powerful symbols of resistance during periods of social and political upheaval. He connected the radical origins of the French and American flags to the need for a new symbol to represent the Gay Liberation Movement. Baker said:

“I thought of the original American flag with its thirteen stripes and thirteen stars, the colonies breaking away from England to form the United States. I thought of the vertical red, white, and blue tricolour from the French Revolution, and how both flags owed their beginnings to a riot, a rebellion, or a revolution. […] As a community, both local and international, gay people were in the midst of an upheaval, a battle for equal rights, a shift in status in which we were now demanding power – and taking it. This was our new revolution. […] It deserved a new symbol.”

The rainbow has broad genealogies that extend beyond its significance as a natural phenomenon, particularly in mythology, religion, and art. By not trademarking the design, Baker acknowledged that a single symbol is not capable of representing a diverse and ever-evolving community. This gesture has allowed members of the LGBTIQA+ community, including Baker himself, to revisit, critique, and reimagine the rainbow flag.

Some claim that the flag is still “connected to a “moderate” or white LGBTIQ movement”, representing only white gay men and lesbians, and excluding queer people of colour, and transgender, bisexual, and other identities and subcultures. To better account for these identities and subcultures, variations of Baker’s original design have emerged.

In 2017, Philadelphia’s Office of LGBT Affairs commissioned the production of a version of the flag incorporating a black and brown stripe to represent the city’s LGBTIQA+ people of colour. The same year, Baker returned to the flag’s original design and added a ninth, lavender stripe to represent the diversity within the queer community. In 2018, graphic designer Daniel Quasar conceived of a version with a chevron at the flag’s hoist, consisting of white, light pink, light blue, brown, and black stripes, to more prominently represent the LGBTIQA+ community’s most marginalised members – people who identify as transgender, people of colour, and those living with or lost to AIDS. Quasar intentionally made a clear visual distinction between Baker’s original design and his additions to ‘shift the focus and emphasis to what is important in our current community climate’. In 2021, designer Valentino Vecchietti built upon Quasar’s design to include and acknowledge intersex people. Vecchietti worked with Intersex Equality Rights UK to conceive of a design that embeds the intersex flag’s design – an expanse of yellow with a purple circle at the centre – within the chevron of white, light pink, light blue, brown, and black.

The evolution of the rainbow flag illustrates its dynamic nature and its ability to adapt to the needs and identities of the LGBTIQA+ community. From its inception as a symbol of resistance and pride, the rainbow flag continues to be a powerful representation of diversity, inclusion, and the ongoing fight for equality.